Process

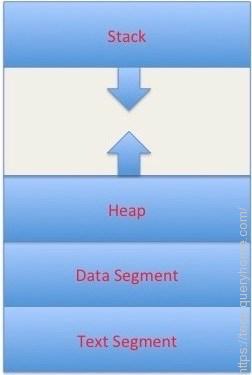

A process is an executing instance of a computer program. We say instance because we may have multiple copies of the same program running simultaneously. How does a process layout look like when loaded into memory for execution ? It is divided into four sections as follows:

Text section contains compiled code of the program logic.

Data section stores global and static variables.

Heap section contains dynamically allocated memory (ex. when you use malloc or new in C or C++).

Stack section stores local variables and function return values.

Stack and heap sections grow in opposite directions as shown in the figure below.

Memory Layout

Figure 1. Process Memory Layout

The OS maintains a special table called process control block (PCB) to keep track of process state. PCB table contains various information about the process, however for the sake of discussion, just keep in mind two items: program counter (PC) and CPU registers. Program counter points to the next instruction to execute and CPU registers hold temporary execution information such as instruction arguments. In short

Process = [Code + Data + Heap + Stack + PC + PCB + CPU Registers]

Thread

A single process may spawn multiple threads of execution. What does that mean ? Let us explain it in two different ways. Intuitively, imagine a web server responding to multiple requests simultaneously. Unless each request is served using a separate thread of execution, one request is going to get the attention of the web server while the others will be blocked. From an OS perspective, just like a process, a thread has a private stack, program counter and a set of CPU registers. Think of it as a lightweight process because it shares code, data, heap and open files with the parent process. In short

Thread = [Parent Code, Data and Heap + Stack, PC and CPU Registers]

Context Switching

In a single processor system, there is no real multitasking. CPU time is shared among running processes. When the time slice for a running process expires, a new process has to be loaded for execution. Switching from one process or thread to another is called context switch. Process context switch involves saving and restoring process state information including program counter, CPU registers and process control block which is a relatively expensive (in terms of CPU time) operation. Similarly, thread context switch involves pushing all thread CPU registers and program counter to the thread private stack and saving the stack pointer. Thread context switch compared to process context switch is relatively cheap and fast as it only involves saving and restoring CPU registers.

Thread Management

We have learned what a process, thread and context switch mean. How is this related to the definition of user and kernel level threads ? Let us see how.

A thread is a sequence of instructions.

CPU can handle one instruction at a time.

To switch between instructions on parallel threads, execution state need to be saved.

Execution state in its simplest form is a program counter and CPU registers.

Program counter tells us what instruction to execute next.

CPU registers hold execution arguments for example addition operands.

This alternation between threads requires management.

Management includes saving state, restoring state, deciding what thread to pick next and why?

Thread management decides thread type. User level threads are managed by a user level library and kernel level threads are managed by the operating system kernel code. To better understand the difference between user level code and kernel Level code, refer to the following article. It explains the difference between user level calls and kernel system calls.

User Level Threads

As we indicated earlier, user level threads are managed by a user level library however, they still require a kernel system call to operate. It does not mean that the kernel knows anything about thread management. Not at all, It only takes care of the execution part. The lack of cooperation between user level threads and the kernel is a known disadvantage. In this case, the kernel may not favor a process that has many threads. User level threads are typically fast. Creating threads, switching between threads and synchronizing threads only needs a procedure call. They are a good choice for non blocking tasks otherwise the entire process will block if any of the threads blocks.

Kernel Level Threads

Kernel level threads are managed by the OS, therefore, thread operations (ex. Scheduling) are implemented in the kernel code. This means kernel level threads may favor thread heavy processes. Moreover, they can also utilize multiprocessor systems by splitting threads on different processors or cores. They are a good choice for processes that block frequently. If one thread blocks it does not cause the entire process to block. Kernel level threads have disadvantages as well. They are slower than user level threads due to the management overhead. Kernel level context switch involves more steps than just saving some registers. Finally, they are not portable because the implementation is operating system dependent.

Thread Models

Let us recap, we have learned that a process may spawn multiple threads. We also said a thread can be user level or kernel level depending on whether a user library or the OS kernel is managing it. There is still something missing here: thread models. Let us talk about that.

Many-To-One Model

User level threads (explained earlier) follow the many to one threading model. This means multiple threads managed by a library in user space but the kernel is only aware of a single thread of the process owning these threads. For example, If the currently running thread blocks for input then all other threads are blocked. For the same reason, the kernel is not going to be able to distribute the other threads on other CPUs if the system has more than one.

One-To-One Model

Similarly, kernel level threads (explained earlier) follow the one to one model. Process threads are managed by the kernel so there are separate kernel threads for each process thread. Since the kernel is aware of all threads, if one thread blocks it does not affect the others. Also, threads can run on different CPUs or cores. Finally, the management overhead is significant.

Many-To-Many Model

This model is the rarest of the implementations. It multiplexes many user level threads to many kernel threads. The goal is to get the benefits of the other models without the downsides, however there is no such free lunch in life so it comes with an implementation difficulty. This article is not the best place to get a better idea about threading models. I just shed some light so that user level and kernel level threads are discussed in context.

Summary

A process is an instance of a running program. Process layout in memory consists of four main sections [Code, Data, Heap, Stack, PC, PCB, CPU Registers]. Like a process, a thread has its own private stack, program counter, CPU registers. A thread shares code, data and heap with parent process. In a multitasking environment, alternating CPU between processes or threads is called a context switch. It is simply saving and restoring execution states. State in its simplest forms is what instruction to execute next and what arguments (i.e. program counter and CPU registers). Managing context switches can be done in user level code through a user space library. In this case, threads are called user level threads. If threads are managed by the OS kernel, then they are called kernel level threads. Multithreading implementation follows certain threading models. User level threads are an example on a many to one threading model. Kernel level threads are an example on one to one threading model. Many to many threading models attempt to get the advantages of both without the downside but the implantation is of a challenge.